The Collegiate Call

Episcopal Collegiate School

Film Student Reflects on Medical Ethics of Kazuo Ishiguro’s “Never Let Me Go”

by Milo McGehee ’17

What is cloning? What constitutes someone or something as human; is it our biology, or something vastly different? What defines the line between ethics and morality, and how does one apply those concepts to contemporary problems? Does human life have value beyond what one gives it, and if so, how do we judge that value? Is it immoral to use human life as a means to an end? To what extent should a patient leave his or her  treatment in the hands of a professional? These questions and more were brought up during a film studies class this past Thursday by guest speaker Micah Hester, a medical ethicist from UAMS (photo above). The lively discussion was based on the class’s recent reading of Never Let Me Go, a novel by Kazuo Ishiguro that was also adapted into a 2010 film directed by Mark Romanek.

treatment in the hands of a professional? These questions and more were brought up during a film studies class this past Thursday by guest speaker Micah Hester, a medical ethicist from UAMS (photo above). The lively discussion was based on the class’s recent reading of Never Let Me Go, a novel by Kazuo Ishiguro that was also adapted into a 2010 film directed by Mark Romanek.

Hester’s duty as a medical ethicist is to help individual patients and families solve ethical problems that arise throughout one’s treatment. This complicated job is rooted in the study and application of philosophy, and in this case, ideas stemming from philosophers such as Immanuel Kant and Jean-Jacques Rousseau. A common conundrum of a medical ethicist is that of organ transplantation, which is a major theme in Ishiguro’s novel; Never Let Me Go uses a not so huge stretch of the imagination to establish a world in which possibly unethical means are used in order to justify an end.

The purpose of this discussion was not purely to allow further reflection of the class’s studies, but to open each student’s eyes to a whole new realm of medicine and philosophy that was previously unknown. As our generation takes a great leap into the future of our species, we take the biggest leap in history. The dawn of this transition, although wonderful and astonishing, leaves many questions to be answered, by students, teachers, and medical ethicists alike.

Making Sense of the Senseless

by Fletcher Carr, Head of the Upper School

As I drove home from school on Friday afternoon, the news reader on a local FM station announced that there had been a shooting in Paris. My first thought was that there had been an incident in Paris, Arkansas. Then I heard the additional details about the French president, the soccer match, restaurant shootings, and an ongoing hostage situation at a concert venue. That evening, in the autumn air of Bald Knob, more news began to trickle–and then flood—in; body counts rose, details clarified, and as always following any atrocity, a set of too-familiar emotions cycled through me: shock, fear, anger, sadness, revulsion, frustration.

As I drove home from school on Friday afternoon, the news reader on a local FM station announced that there had been a shooting in Paris. My first thought was that there had been an incident in Paris, Arkansas. Then I heard the additional details about the French president, the soccer match, restaurant shootings, and an ongoing hostage situation at a concert venue. That evening, in the autumn air of Bald Knob, more news began to trickle–and then flood—in; body counts rose, details clarified, and as always following any atrocity, a set of too-familiar emotions cycled through me: shock, fear, anger, sadness, revulsion, frustration.

Over the weekend, as I watched and read commentary that simultaneously untangled and re-tangled the events, I thought back to the same early responses to September 11 and recalled how many of the initial declarations had been grounded in faulty information and understandable hysteria. I also reflected on the students I had sat with in my writing class on 9/11 and about our conversations as the events unfolded. The conversations were not deep, but they were meaningful in that they were happening. More than anything, we talked about the terror behind terrorism and what the perpetrators were trying to achieve. And most importantly, we talked about how we thought it might impact our feelings and our lives.

And as the conversation evolved over the days following our nation’s own tragedy 14 years ago, the dialogue seemed to boil down to the question of response. After hearing the stories and seeing the results of this attack, students wrestled with how they should respond. Some wanted to respond with violence against violence; others looked at what they saw as the futility of violence in response to violence. And now, almost a decade and a half later, we are facing just that same question.

Grant Lichtman, a dynamic and forward-looking American educator and author of the blog, The Future of K-12 Education, posed this question beautifully in a post on Saturday, writing, “In the aftermath of Paris, people of good will are wrestling with perhaps the existential question of our time: can we fight our way to peace, or does the solution lie in following those greatest teachers of our time—Gandhi and King—who argued that we can never “drive out darkness with darkness in kind, but only with light”?”

As we struggle with this newest iteration of geopolitical and ideological violence, I know that I don’t have a ready answer. But I hope that the offer of conversation, among families or within the classes and daily routines of the Episcopal Collegiate Upper School, can begin to help students place this horrific event in context and begin to shape their own responses to the questions, at all levels, raised by this event.

And even if the conversation is halting and unsettled, which it likely will be, the recognition that we all currently share the same anger, fears, and uncertainty can mean everything as the young people in our community work to process and make a semblance of sense of the senseless.

Note: Common Sense Media, a media watchdog agency dedicated to children (toddlers to teens) published the following guide over the weekend to help parents talk with their children about news stories such as this one: https://www.commonsensemedia.org/blog/explaining-the-news-to-our-kids

How to Help Your Child With Writing Without Overstepping Boundaries

By Vivian Blair, Upper School Creative Writing

Writing is a craft, and to get better at writing, students must write frequently. It’s a process, and each student needs to do the work required to get better. Parents often ask teachers if they can help their children with writing without overstepping appropriate boundaries, and the answer is “yes, of course!” Parents can use these four tips to help as writing partners.

Writing is a craft, and to get better at writing, students must write frequently. It’s a process, and each student needs to do the work required to get better. Parents often ask teachers if they can help their children with writing without overstepping appropriate boundaries, and the answer is “yes, of course!” Parents can use these four tips to help as writing partners.

Tip 1: Help writers rehearse their structure. Ask planning questions about sequencing and correlations, such as “Where is your thesis statement?” or “What is your plan for organizing this essay?” It’s okay to write down what the student says, but resist the urge to “clean it up” or use “better” or “bigger” words. It has to sound like the student, not like a parent.

Tip 2: Help writers elaborate. Ask “What do you mean here?” or “Can you explain this more?” Students tend to say more than they write, so when they explain, the reader is more able to follow their line of thinking. Again, transcription is acceptable, but resist the urge to give them words. Use the student’s words.

Tip 3: Work with the examples, rubrics, and checklists given to the student. Most teachers provide students with examples and rubrics for writing assignments. Remind your student to check his/her essay against those examples and rubrics.

Tip 4: Unless research is specifically required, remind students to avoid the Internet! The work needs to reflect the student’s thinking—not the parent’s thinking or the thinking of someone else.

Writing is hard because writing requires thinking. Teachers know the students will struggle with these concepts. The goal is to improve the student’s writing, and the good news is that it is in the struggle that they learn and improve!

Kindergarten Matters

By Cole Lester, Head of the Early Childhood School

Kindergarten is an escalating, interdisciplinary learning process in which children imagine what they want to do, create a project based on their ideas (using blocks, finger paint, or other materials), play with their creations, share their ideas and creations with others, and reflect on their experiences—all of which leads them to imagine new ideas and new projects.

Kindergarten is an escalating, interdisciplinary learning process in which children imagine what they want to do, create a project based on their ideas (using blocks, finger paint, or other materials), play with their creations, share their ideas and creations with others, and reflect on their experiences—all of which leads them to imagine new ideas and new projects.

As kindergarten teachers consider learning expectations (“the what”) and plan for their students (“the how”), they infuse each day with developmentally-appropriate practices. They use a wide variety of teaching strategies, such as asking questions, fostering dialogue, offering choices, linking the new to the familiar, and using rich vocabulary. They individualize student learning, providing the least amount of support that each child needs to achieve a learning goal. They use a variety of teaching styles, thinking carefully about which learning context or format is best for helping children achieve a desired outcome. They incorporate countless assessment strategies in an effort to get to know each child and his or her current and changing abilities, needs, interests, and unique learning styles.

There is something undeniably compelling about this cognitive description- the learning world it describes is so arranged and linear, such a clear case of inputs here leading to outputs there. However, educators know that success does not depend primarily on cognitive skills, the kind of intelligence that gets measured on IQ and achievement tests.

If we want children to truly learn, to process and internalize information, we have to let them play. Through play-based learning and creativity, young children learn non-cognitive skills such as conflict resolution, problem solving, higher-level thinking, character- persistence, self-control, curiosity, and self- confidence.

That is why, embedded in our curriculum, you will see these equally (arguably more) important learning expectations for kindergarteners:

- Learn by example to follow school and classroom rules and to act in an honest and responsible manner

- Engage in purposeful play and directed discovery

- Develop a sense of integrity and core values

- Understand the consequences of actions

- Build self-esteem by facing challenges and experiencing success individually and with the help of others

Kindergarten has historically been a place for telling stories, building castles, painting pictures, making friends, and learning to share.

Kindergarten has historically been a place for telling stories, building castles, painting pictures, making friends, and learning to share.

Globally, kindergarten is undergoing a dramatic change. In some kindergartens today, children are spending more and more time filling out worksheets, drilling flash cards, focusing on rote memorization, and having their learning assessed in a standardized manner. In short, kindergarten is becoming more like the rest of school.

If you walk down the kindergarten hallways at Episcopal Collegiate School, you would agree that the opposite needs to happen: We should make the rest of school (and life) more like kindergarten. Let them play.

A Bad Tweet Lasts Forever!

Clueing Into Social Media

by Katherine Robinson, Technology Integration Specialist, and Mary Brook-Townsend, Middle School Librarian

Typically, Middle School is a time of tremendous growth for our students. Changing schedules, teachers, expectations, and social circles are all common to this stage of life. Of equal importance is how social media plays a key role in our student’s communication with one another. Making sure they are respectful and responsible in their use of social media, as well as understand the positive and negative consequences of social media, plays a major role in our advisory program.

During the first quarter, each grade level participated in focused lessons and discussions centered on the acronym THINK. This acronym provides simple questions students can ask themselves before they post to social media, send a text message, or email. Additionally, the questions were used to jump start important conversations about oversharing, cyberbullying, and inappropriate content.

Our 6th grade class centered their lessons on the negative consequences of sharing inappropriate content online. Students discussed the idea that the Internet never forgets and the importance of being mindful of how their digital footprint impacts their reputation. Their second lesson focused on the roles students play in cyberbullying situations. Students were asked to read and discuss cyberbullying situations, identify the bully and the victim, and brainstorm ways in which the bystanders could have been upstanders and involved a trusted adult.

The 7th grade class focused their discussion on the idea that oversharing can have negative consequences on their social lives and reputations. Their conversation centered on the Common Sense Media video, Oversharing: Think Before You Post and how our state law enforcement agencies are currently responding to cyberbullying.

Eighth graders began their discussion by looking at the study, Social Media, Social Life: How Teens View Their Digital Lives. This study highlighted that one in five teens feel that social media made them more confident and that 52% of teens believed that social media had improved their friendships. Using this research, they discussed how poor decisions when posting online and the consequences surrounding those decisions could shift that perspective.

To continue these discussions at home, we recommend the resources available on Common Sense Media particularly the social media “tip sheets”.

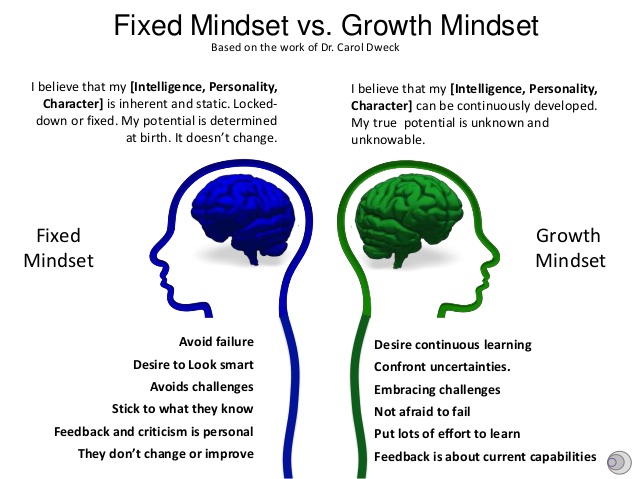

Fixed vs. Growth Mindset

Episcopal Collegiate Counselors Tricia Davis and Anna TerAvest recently introduced students to Carol Dweck’s research on fixed vs. growth mindset. Her research found that the way children are praised sends a distinct message and creates a strong mindset about abilities. When children are praised for accomplishments, they tend to stick to easier problems and shy away from challenges. This is a fixed mindset. They begin to believe that the talents and intelligence they are born with is all that they will have. When children are praised for effort and hard work, they begin to seek out more challenging material and realize they can grow their talents and intelligence. This type of thinking is called a growth mindset.

We asked our students to examine where they have fixed mindsets when they say things like:

I don’t need to study; I always do well on math tests.

I can’t draw.

I’m not a writer.

We asked them to change the way they look at this self-talk and instead use wording like:

Studying can help prime the brain for future growth. I need to let my teacher know that I am ready and willing for more of a challenge.

I’m still learning to draw. The more time I spend drawing and learning from others, the better I will be.

My writing is not polished and smooth, yet, but I keep writing and rewriting.

Parents can help their children immensely by paying close attention to the wording they use when praising children. The words and actions we use towards them shape how they think about themselves. The following lists give some examples of how to praise your child to create a growth mindset.

Fixed Mindset Language to Avoid

You are really athletic!

You are so smart!

Your drawing is wonderful; you are my little artist.

You are so fast! You will be the next Usain Bolt.

You always get good grades; that makes me happy.

Growth Mindset Language to Use

You really work hard and pay attention when you are on the field.

You work hard in school, and it shows!

I can see you have been practicing your drawing; what a great improvement.

Keep running, and you will see great results.

When you put forth effort, it really shows in your grades. You should be so proud of yourself. We are proud of your effort.

So, the next time you are ready to praise your child, stop to think about how to use that opportunity to praise his or her effort instead of accomplishments. Also, please help them rephrase their “I can’t” to “I’m not there, yet.”

A Grand Trip to the Tetons

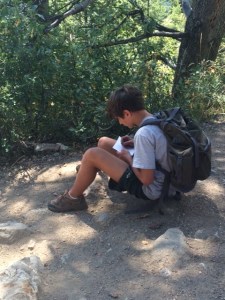

In August, Episcopal Collegiate ninth graders journeyed on an Upper School pre-orientation trip to one of the most beautiful landscapes in America – the Grand Teton Mountains. The students spent four nights and three days at the Teton Science School in Jackson, Wyoming. Students documented their adventure, which included hiking, journaling, water-quality testing, and wildlife observation, on their blog: http://www.tetonscience.blogspot.com/search?updated-min=2015-01-01T00:00:00-08:00&updated-max=2016-01-01T00:00:00-08:00&max-results=40 For a closer look, we asked Episcopal Collegiate School Freshman Boyd Bethel (shown below journaling on the trip) to tell us more. Thanks, Boyd! Read on . . .

Going on the trip to the Grand Tetons was really a fun and engaging experience for my classmates and me. After lengthy airport layovers and a light dinner, the tired (and hungry) crew of students finally arrived in Jackson, Wyoming to be bused over to the Teton Science Schools.

Going on the trip to the Grand Tetons was really a fun and engaging experience for my classmates and me. After lengthy airport layovers and a light dinner, the tired (and hungry) crew of students finally arrived in Jackson, Wyoming to be bused over to the Teton Science Schools.

As we scrambled to get in as much iPhone time as possible before our devices were confiscated, bright screens lit up and heart-breaking goodbyes were said to social media.

Without our phones to distract us, we listened for our dorm and room assignments. The girls received rooms with showers, while the boys settled for a clear downgrade: community showers. After we had settled in before bedtime the first night, we finally collapsed, exhausted from the day.

Morning came early, and Coach Marsh and Coach Friedel didn’t hesitate to force the guys out of bed, which I wasn’t crazy about. When breakfast ended, we broke into our designated animal groups: Pronghorn, Otters, Wolverines, and Moose. We then went on hikes and began our journey to learn more about science. Before the hike, however, we were told that if we had to “chase any bears or coyotes,” we were allowed to do so. Initially confused, I wondered what this meant, only to be shocked when I heard it was simply a euphemism for using the restroom. Anyway, with this strange, useless bit of knowledge, I continued on the hike with my fellow Pronghorns, enjoying the Rocky Mountains and learning science.

This was only the beginning, as we would continue this process of waking up way too early, visiting and hiking through scenic parks like Yellowstone, and playing pick-up basketball during free time (with courtside commentary from Madison Marsh and Madison Dixon).

The Tetons were a great place for my class to bond, especially with the science school’s emphasis on leadership. This has really helped to instill confidence in every one of us incoming ninth graders to be the best person possible, both in and out of class. It has also helped encourage class cohesiveness as we begin our Upper School journey.

The Tetons were a great place for my class to bond, especially with the science school’s emphasis on leadership. This has really helped to instill confidence in every one of us incoming ninth graders to be the best person possible, both in and out of class. It has also helped encourage class cohesiveness as we begin our Upper School journey.

Overall, I greatly enjoyed every aspect of this trip (save the stomach cramps from eating Panda Express; thanks, Martin) and appreciated the opportunity to learn and make lasting friendships. I can already tell it’s going to be a great year with this group. Go Wildcats!

The Value of Making Mistakes

By Fletcher Carr, Head of Upper School

About three years ago, I read an interview conducted with Drew Gilpin Faust. Dr. Faust is an historian who has written many wonderful books and articles that I have read and shared with my history students over the years; she also happens to be the president of Harvard, which this year enters its 380th year of existence. In this interview, Dr. Faust was asked what book she would recommend to entering students at Harvard, and she did not hesitate, answering that she would ask that these accomplished young students read the book, On Being Wrong: Adventures in the Margin of Error by Kathryn Schultz. Schultz’s book was the first volume in a recent flurry of books that examines the ideas of error and making (and learning from) mistakes. In the last three years, other books, Better By Mistake: The Unexpected Benefits of Being Wrong and the very recent contribution to the genre of what is being called, in Schultz’s words, “wrongology”, The Gift of Failure: How The Best Parents Let Go So Their Children Can Succeed have made similar arguments.

Ultimately, these books are all exploring the fears of failure that, on many levels, can destroy what should, in students, be an innate love of and curiosity about learning and discovery. And there are so many factors as to why we have reached this point: an ever-growing population of high school graduates heading to college, combined with a relatively unchanging number of spots open at very competitive colleges, has made the stress of getting into these schools almost unfathomable, and as a consequence, the ripple effect that this demand creates moves along the chain to nearly all levels of college admission. This game of numbers has also been impacted by national reform movements in education over the last 30 years. As I entered the education sector in the mid-1980s, there was an increasing emphasis on developing self-esteem in students, particularly at a young age. The idea behind this movement was that if students felt good about themselves, they would not be afraid to make mistakes and would thus like and succeed in the process of learning. With this movement came many ideas, one of the best known being “participant” recognition, which gave rise to the dreaded participant trophy that highlighted the notion that all competitors are more or less equal, and that as long as everyone has fun and feels good about themselves, then any event that included living, breathing people could be considered a success.

Since its introduction to education, this idea has run up against the realities of a world that is vastly changed—a world more competitive, flattened by technology, and perhaps less patient with the warm-fuzzies of self-esteem when set against the fierce realities of the global marketplace. And certainly, there has been a backlash against this rather humane idea—as a nation, we have been criticized for creating a generation of students who are simply happy to be here. Real learning, the critics of this movement say, comes from having to work to earn excellence—to these folks, self-esteem does not come from liking yourself, it comes from mastering subjects and skills.

With the stakes seemingly higher and higher, however, the margin of error mentioned in the title of Schultz’s book seems to be getting smaller and smaller, particularly in schools. A decade or so ago, I had the opportunity to visit my undergraduate college and attend the classes of several of my former professors. Like any alumnus, I am proud of my college–the students there have remarkable high school resumes—certainly much more polished than those in my graduating class years ago could boast. In sitting in on the classes, however, I noticed something—the class discussions were flat and unadventurous. As I drove home from my visit, I wondered if my memory was playing tricks on me and if I was embellishing what I recalled as the fun and much more lively class dialogues from my college years. So, I called one of the professors as well as a former classmate who was now teaching there and asked if what I was sensing was right. They both agreed, theorizing that the process of gaining admission to a highly competitive college exerts a tremendous amount of pressure on students to follow a virtually errorless high school path—and that the habit of avoiding mistakes has led to increasingly tentative students who are extraordinarily able in virtually every facet of their lives, but are also extraordinarily concerned about making mistakes or putting themselves out there. The books that I have read recently—and Harvard’s president’s recommendation that the incoming students read that book on being wrong, however–tells me that others are also seeing this pattern.

So, if this is a pattern—and if you recognize it in yourself or in others, what do you do? The making of mistakes is a complex and fascinating topic—St. Augustine famously proclaimed that “to err is human”; and Schultz includes in her book a wonderful observation by Ben Franklin, who noted in 1784 that “…the history of the errors of mankind is more valuable and interesting than that of its discoveries. Truth is uniform and narrow…but error is endlessly diversified; it has no reality, but is the pure and simple creation of the mind that invents it…” Many argue that our reactions to mistakes are cultural, others argue that the reactions are based on individual responses and our own cognitive development—whatever the case, making mistakes is profoundly human. Harder, but still human, are our attempts to disguise our errors or to hold onto a view that has clearly been proven wrong.

The topic is an enormous one, given the ways in which we can be wrong; we can be part of a small and funny “comedy of errors” or we may—hopefully rarely or never–be part of a much more serious error. Often it is those individuals and organizations in high-risk areas, such as airline companies or the military, who drive some of the best research in risk analysis and error prevention. But nearly any business enterprise, by virtue of its research and development process— a process that actually encourages and budgets for errors and experiment—works heavily in the wrongology department. In her book, Schultz notes that three common themes have emerged from many of these studies: first, that organizations should have a “tolerance for failure” built in. In many organizations, that tolerance is the research and development program; in schools, maybe that margin exists in draft papers, series of experiments, or advisory meetings that discuss good decision-making. The second common theme is the openness of the organization to error-making and a commitment to the transparency of the procedures in place at all levels—in that way, all can see where mistakes may take place and have a hand in correcting them. And lastly, hard, verifiable data is critical to pull the humans in the organization away from their “human-ness”. Often, our own biases and opinions can make us the type of person who my grandmother would often drily refer to as “often in error, but never in doubt”, or in other words, the person who pushes through wrongheaded ideas with little pause for reflection. There are many ways that our minds will get behind an incorrect idea and stay with it beyond all rational measures.

Making mistakes and learning from them is also something that has much to do with your own mind-set—or the set of attitudes that you have established for the way you learn and develop. Ms. Davis and Ms. TerAvest will be looking in more detail at that important concept with you as the year progresses.

More than anything, though, you can simply be aware of those areas at school and in your life where you make mistakes (and I am assuming from my own experience in life, that that is every area!)—and how you can recognize them and develop that tolerance for failure, process through your fear of making mistakes and figure ways to learn from them, and lastly simply own and articulate them. The more that you and your classmates and all of the members of the community can do this, the easier and less worrisome the process will seem—and when you have gotten to that point, watch out—great things can happen.

This summer, I attended a workshop directed by faculty members from Stanford University’s Design School, a program at the university that focuses on ways to look differently at how we think and create things. On the first day, the director of the program announced that she had a very important question to ask all of us before we started the process. So, I waited for what I assumed would be a lofty, philosophical question about the nature of the creative process. The director waited a second as the room grew silent and then asked: “What does a clown do when he or she makes a mistake?” A few mumbled replies could be heard.

“A clown,” she continued, “bows deeply and says ‘Ta Da!’” In other words, clowns recognize a mistake, own it, and move on. My group at the workshop actually did a lot of this during our design sessions and it was quite effective; the rather silly action of bowing and saying ‘Ta Da’ made mistakes seem less dreadful and thus more easily dealt with.

So, here’s to a lot of loud and proud ‘ta-das’ this year and over the course of your lives—good luck, let your voice be heard– wrong or right–and find your answers!

Episcopal Proud

The following letter was written to Episcopal Collegiate Middle School Head Chip Parks and Interim Lower School Head Elizabeth Desmarais by Wendy Ward, the mother of 6th grader Mirielle Clayton.

October 24, 2014

Mr. Parks and Ms. Demarais,

My daughter plays football for the 5th/6th grade Episcopal Wildcats team. I am writing this from the stands as they warm up for their first playoff game. I am filled with so much gratitude for this school and the teachers, administrators, parents, and coaches within it. I would like to share with you her story and to highlight along the way the many people who have been supportive.

It all started when basketball season ended in Winter of 2014. Mirielle plays on the girls basketball team and during recess she and several of her friends played basketball with the boys. When basketball season ended the boys started practicing football at recess. She asked to play and they told her that ‘girls can’t play football.’ It was the word ‘can’t’ that bothered her, I think. She apparently studied the problem for a while and then a few weeks later I got a call from a teacher at the school who told me, confidentially, that she supported Mirielle’s petition 100%. My reply was….what petition? She had 50 signatures (teachers, parents, students) on a handwritten petition that said “Girls should be allowed to play football.” I had no idea! We had a long talk about her desire to play, that a petition may not be necessary, and that maybe we should just ask. So I made an appointment to talk to Ms. Kennedy, the Head of the Lower School.

Ms. Kennedy reported that she was not aware of a reason why she couldn’t try out but that she would ask. I gather there was a meeting, the league was consulted, and in the end we were told that she could play. We were given a few fairly humorous (and anonymous) reminders. First, we were told that if she needed any special equipment, we would need to purchase it ourselves (her PCP told us nothing was required at this age). Second, we were reminded that this was tackle football not flag football. I certainly hope whomever that reminder came from has seen her play. She plays Defensive Tackle and Offensive Guard and I have seen her sack the quarterback – twice in one game! She holds her own out there. Yes, yes, she is aware this is tackle football. Finally, and this is my favorite, we were reminded that there is no crying in football. Well, I just had to laugh out loud when I heard that one. I’ve watched every Super Bowl for the last 30 years. As I recall, there is a LOT of crying in football.

Once Mirielle knew she was able to play, she told me her plan; Because of course she had a plan. She was certain the boys had played several years already and she needed to catch up. She asked me to enroll her in two football camps during the summer (which I did, Episcopal’s and Pulaski Academy’s camps). She also asked to watch football replays with her step-father so he could tell her about the plays and strategy. Which she did. She was nervous but prepared on the first day of football practice.

Coach Jemerson and his team of coaches are volunteers–parents of kids who are playing. I cannot thank them all enough for the culture that they have built on this team. They have provided a culture of equality. She is worked just as hard as the boys, praised when she does well and given feedback when she makes a mistake, just like the boys. She feels such pride when she says she is part of the team. Issues that could have been a problem (like the locker room) were clearly worked out before she got there–when I asked her about it, she looked at me like that was a ridiculous question–of course she and the coaches waited 5 minutes for the boys to change and then they all went in for a locker room talk. She has a locker in there for her helmet and pads,just like the boys. She changes at home later. Not one problem situation has arisen. Not one. I thank Coach Jemerson and his team for that. I was so very happy that they interviewed him for the news, not just her. What he said for the cameras was totally true. When he heard a girl was trying out for the team, he was excited–the more players, the better. Period. What a powerful statement.

Mirielle also speaks very highly of Coach Seale, the line coach, who has worked most directly with her this year teaching her blocking strategies. I was there when he asked her to play Guard. She was so happy and excited! He also has her playing Defensive Tackle and for many of the games she played almost the entire time. He tells the line that even though the quarterback and receivers often get the credit for the scores, it takes everyone on the team to win a game. If the line doesn’t hold, the quarterback and receivers can’t do their jobs. In fact, she quotes him all the time— ‘it takes an entire team to win a game, and only one person not focusing on their part to lose a game.’ These are life lessons being learned during practice. Important life lessons that will last a long time. In the end, she is stronger, more skilled, and thinks more strategically now. And she knows her coaches gave her those skills. She speaks so highly of them all. With this kind of support and encouragement–she has put her whole heart into it. She is just filled with energy and enthusiasm for every practice, every game.

In an era when youth can get pretty full of themselves pretty quickly, I can honestly say that Mirielle has stayed pretty grounded through all the attention she has received. She was a bit bewildered that several pre-K students keep asking to get their picture taken with her in uniform. She was confused by the media attention and wasn’t sure what to say. She has told me multiple times that she just wanted to play and now that she does she is just part of the team, so what is the big deal anyway? She has grown up not seeing barriers, limitations, and inequalities. The culture at Episcopal is a big part of that. Yes, the boys told her girls can’t play football and teased her a bit at first. But Day 1 of the first Episcopal football camp one of the coaches of the summer camp (different than the current coaches but nonetheless important) overheard and told the boys they were being sexist, that she was as good as they were at the skills, and they should be glad to have her on the team (fyi – she thought the word sexist was one she was not allowed to say out loud, so she spelled it for me. Hilarious.). That was the end of the boys’ comments about girls not being able to play.

I do not diminish my child’s grit and determination when I say that who she is as a person is a reflection of the experiences she has had growing up including not just her coaches in summer camp and the current season, but also some important interactions with the teachers at Episcopal. Her current teacher, Ms. Schallhorn has taught her the value of creative thinking–thinking outside the box, approaching solutions from a different angle. Ms. Jennings (fourth grade) taught her about government and avenues of social and political change (hence, her petition last year). Ms. Feland taught her the importance of challenge and how to approach problems positively and systematically. Ms. Nichols taught her the value of self-reflection–thinking through her own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors with an eye toward the kind of person she wanted to be. Ms. Scanlon in first grade taught her the love of learning–the beginning of her avid reading hobby with her first chapter books, the applied math, understanding history and the world. And our beloved Ms. Fortenberry who was her first teacher in the Lower School and also the teacher she had the year her father died. She gave her the gift of love and acceptance upon which her self-confidence to this day is built. Not to mention the science, math, choir, reading, Spanish, PE, chapel, aftercare staff, and other meaningful learning experiences along the way.

When I watched the gym erupt at the Lower School pep rally when Coach Jemerson introduced Mirielle as the “most physical player “ on his team, I was overwhelmed with the notion that she is not the only one who has benefited from her playing. The female students in the room will hopefully take this experience and apply it in their own lives–perhaps they will enter fields of science, subspecialties of medicine, other areas where women are underrepresented, or seek leadership roles uncommon for women to hold. The male students in the room will hopefully take this experience and apply it in their own lives–bringing acceptance and a sense of equality and teamwork into board rooms, science labs, and medical fields.

As I sit here while the team is warming up, I recognize that I want our team to win. Win! Yet at the same time I know that regardless of how the game ends, we have already won. My daughter Mirielle plays football. But the real story is the culture of the school she plays for and the teachers and coaches and administrators who have supported her all of her years there. The real story are the boys who are her teammates who play with her and accept her, and the parents and students cheering for her and for the team in the stands. The real story is what comes next–when these students all grow up and take their places in the world. Who knows what powerful good can come from such a simple thing as letting a girl play football.

Grateful,

Wendy L. Ward, Ph.D., A.B.P.P.

Professor Associate Director of Faculty Affairs

Department of Pediatrics, UAMS College of Medicine

You must be logged in to post a comment.